By Nancy O’Malley, 2013

Free people of color in Bourbon County

Free people of color constituted a very small percentage of the African-American population in antebellum Kentucky. In Bourbon County where the African-American population was one of the highest in the state, women usually made up more than half of the free Black population in any given census year. However, free women of color never exceeded 3% of the total antebellum African-American population in Bourbon County. The minority status of free Blacks in Bourbon County placed them in a highly visible position since most people of color were enslaved and routinely identified by whites as the property of a particular slave owner. Free people of color, on the other hand, could not be so identified which placed them in a nebulous category—not enslaved but also not considered equal to whites.

Table 1. Census statistics for free people of color and the enslaved in Bourbon County, Kentucky

| Status |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

| Free women |

64 |

163 |

160 |

137 |

171 |

| Free men |

66 |

133 |

148 |

108 |

129 |

| Total free |

130 |

296 |

308 |

245 |

300 |

| Slave women |

2570 |

3338 |

3144 |

3433 |

3320 |

| Slave men |

2595 |

3530 |

3181 |

3633 |

3447 |

| Total slave |

5165 |

6868 |

6325 |

7066 |

6767 |

| % free women of total blacks |

1% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

(2004) Historical Census Browser. Retrieved 13 November 2013, from the University of Virginia, Geospatial and Statistical Data Center: http://mapserver.lib.virginia.edu/collections/stats/histcensus/index.htm

When free Blacks appear in public records such as deeds, newspapers, probate documents and the like, their free status was invariably included by the use of terms such as “free colored” or “free man of color” or even, on occasion, attached to a name such as “free Betty.” Whites generally were suspicious of free people of color and harbored prejudicial attitudes that were no less and perhaps even more virulent than their attitudes about those enslaved (Lucas 1992:108). These attitudes hardened over time as slavery became increasingly equated with skin color and African ethnicity. Thus, free women and men of color had to negotiate a tenuous social ground. The situation was further complicated by the variation in skin color, ranging from very dark to very light complexions, that was present among enslaved and free people. These distinctions were expressed by terms such as black, mulatto, yellow, copper and very dark that were used as visual identity markers in runaway advertisements, manumission records or other documents along with descriptions of scars, facial shape or other observable bodily characteristics. Light-skinned people of color occupied an ambivalent racial position—neight white nor black enough to fit unambiguously in a clear-cut category. However, whites tended to view people with lighter skin color, free or slave, more favorably, considering them more capable of “refinement and advance…[and] more susceptible to improvement” (Toplin 1979:194).

The Kleizer Sisters

As part of a larger ongoing project to gather information about free people of color, particularly women, in Bourbon County, Kentucky, the existence of two sisters, Louisa Warren and Mary Malvina Kleizer, was uncovered. Their story is a particularly interesting one—partly because they owned property and were businesswomen in Paris and partly because both sisters eventually “passed for white”.

On June 14, 1836, an inventory was filed in the Bourbon County Court for blacksmith Henry Kleizer who had died intestate, probably on his farm of 147 acres on the Iron Works Road. The inventory included “1 Negro woman and 2 children” valued at $800. On July 4, 1836, Henry’s father, John Kleizer, acting on his son’s request, freed the woman, Jude, and her two daughters, Louisa Warren, and Mary Malvina in an order of manumission that was filed in the Bourbon County Clerk’s office. Jude was described as 42 years old, 5 ft ½ in in height, with a yellowish complexion, open countenance and “altogether rather good looking.” Louisa Warren was 14 years old, 4 ft 10 ½ in in height and Mary Malvina was 12 years old and 4 ft 7 in in height. Both were slender with “bright mulatto” complexions and “good countenances”. Their light skin color suggests that their ancestry included white relatives, most likely white fathers and one or more white grandparents.

Henry Kleizer also owned two enslaved boys, Washington and Silas, to whom he did not grant freedom. He had purchased the two boys, then 4 and 3 years old respectively, along with his farm of 147 acres from Samuel B. Kleizer in 1833. By 1840, Jude was using the surname of Kleizer and heading her own household with her two daughters. In 1840, Jude was one of 30 free women of color in Bourbon County between the ages of 36 and 54 years. Louisa and Mary were among 33 young free women of color between 10 and 23 years. There were only 160 free females in Bourbon County compared to 3144 enslaved females. Jude had to support herself and her daughters; her occupation is unknown but she probably held one of the limited occupations generally filled by women of color, such as cook, laundress, child care or perhaps agricultural labor. Sadly, Jude died of cholera in 1849, leaving her two daughters who by that time were in their 20s.

On May 29, 1850, Louisa and Mary Kleizer purchased a house and lot on Main Street in Paris for $800 from William and Catherine P. Duke. The lot was part of in-lot 14 near the corner of Main and Mulberry (now 5th) Streets. The property corresponds to 428 Main Street where the City Club is now located. The building was flanked by the property of William W. Hughes on the northeast side and Peter Haley on the southwest side. Louisa and Mary were occupying their newly purchased property when they were censused in 1850. Louisa was 24 years old and was not listed with an occupation nor could she read or write. Mary was 22 years old, also without an occupation, but was able to read and write. An 8 year old mulatto girl named Ellen Burch lived with the two sisters and had attended school during the year.

Living next door was Peter Haley, a 56 year old baker. Also living nearby was William Hughes, a 28 year old saddler. Listed with Hughes and his family was George W. Ingels, a 26 year old white stable keeper who owned real estate valued at $1300. His livery stable had an entrance on Main Street that led to the stable area in the rear of the lot which stretched to Pleasant Street. George W. Ingels was the son of Boone Ingels and Elizabeth Reid Ingels. Boone Ingels was born at Grant’s Station on Bryan Station Road near the Bourbon/Fayette County line to James Ingels, Jr. and Catherine Boone Dehart Ingels. George has a second listing under his mother’s household in the 1850 census. His father, Boone, died in 1837 and his mother never remarried. In 1850, she was listed in Paris with real estate valued at $7000. Her household included Edward, aged 28, who was a physician, George W., aged 26 who was not listed with an occupation but had real estate valued at $1300, Mary, aged 20, and Eliza Blandenberg, aged 23.

As other records show, George Ingels began a relationship with Mary Kleizer that resulted in the birth of four children by the next census in 1860. The 1860 census lists the two sisters under the spelling of Cliser, living together in Paris and working as confectioners. Their real estate had increased in value to $1400, split between them, with a combined personal worth of $1000. Mary’s children included Jennie Elizabeth, aged 8, Louisa, aged 5, George W., aged 3 and Mollie, aged 1. Ellen Burch was still living with the sisters. All of Mary’s children were listed with the surname of Cliser (Kleizer) rather than Ingels because, as a woman of color, she could not legally marry George Ingels.

As other records show, George Ingels began a relationship with Mary Kleizer that resulted in the birth of four children by the next census in 1860. The 1860 census lists the two sisters under the spelling of Cliser, living together in Paris and working as confectioners. Their real estate had increased in value to $1400, split between them, with a combined personal worth of $1000. Mary’s children included Jennie Elizabeth, aged 8, Louisa, aged 5, George W., aged 3 and Mollie, aged 1. Ellen Burch was still living with the sisters. All of Mary’s children were listed with the surname of Cliser (Kleizer) rather than Ingels because, as a woman of color, she could not legally marry George Ingels.

In 1867, Mary and George moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, leaving Louisa Kleizer and Ellen Burch in Paris. Williams’ 1868 Cincinnati Directory listed George W. Ingels as a partner in the firm Arnold, Bullock & Co. James L. Arnold, Thomas L. Arnold, W.K. Bullock and George W. Ingels were wholesale grocers, commission merchants and liquor dealers at 49 W. Front Street. In the 1869 directory, George was associated with J.L. Arnold in a coal dealership under the firm name of Arnold & Ingels.

George W. Ingels appears in the 1870 census for Cincinnati, Ohio, living with Mary who assumed his surname as did their children. Mary and her children are all identified as mulatto in this census. Two more children, Hiram, aged 8, and Birchie (a nickname for Burch), a daughter aged 5, had been born in Kentucky since the last census. Elizabeth and George had both attended school within the year, but Louisa was an invalid. George reported his occupation as a retired coal merchant worth $35,000 in real estate and $10,000 in personal estate at the relatively young age of 46.

assumed his surname as did their children. Mary and her children are all identified as mulatto in this census. Two more children, Hiram, aged 8, and Birchie (a nickname for Burch), a daughter aged 5, had been born in Kentucky since the last census. Elizabeth and George had both attended school within the year, but Louisa was an invalid. George reported his occupation as a retired coal merchant worth $35,000 in real estate and $10,000 in personal estate at the relatively young age of 46.

The 1870 census lists Louisa as a notions and fancy goods merchant, and Ellen Burch was working as her clerk. The shop was probably in the building Louisa owned on Main Street. Although the 1860 census indicated that Louisa had married within the year, no evidence was found to indicate that she had a husband and the census may have been in error. However, her husband may have been a slave who would not have been living with her. She is not listed with a husband in 1870; he might have died.

In October of 1880, George and Mary Ingels sold Mary’s half-interest in the Paris Main Street property to Louisa Kleizer for $900. Louisa was living by herself by this time and was listed as a widow without an occupation. No record of any marriage was found in the Bourbon County records for Louisa Kleizer.

The 1880 census record for the Ingels family chronicles a change in how the Ingels children were categorized. Although Mary is still listed as mulatto, all of her and George’s children are listed as white. The family was living on Hopkins Street at the time of the census and were still living there in 1890. All six of their children were living with their parents in 1880. The two oldest, Elizabeth, aged 22 and Louise, aged 18, helped their mother keep house. George at age 16 was a bill-clerk in a store. Hiram worked as an entry clerk. He was 17 years old but the census incorrectly lists his age as 22. Burch, aged 13, and Mollie, aged 9, both attended school. Burch was incorrectly identified as male. George, Sr. reported his occupation as a retired merchant.

Mary and George Ingels lived in Cincinnati for the rest of their lives. By 1900, they were living on Wesley Avenue just a few blocks from their former home on Hopkins Street. The census taker incorrectly spelled their name as Engalls. George reported that he was 76 years old, born in February of 1824 and married for 47 years. He was a landlord. His wife Mary was identified as white rather than mulatto. She was 75 years old, born in February of 1825. Oddly, the census taker listed Germany as the birthplace of both her parents. Other people in the household also had German born parents so this may have been a miscommunication with the census taker but given that Mary appears to be passing for white in this record, it may have been intentional. All of the family members in the household were listed as white. Three of George and Mary’s six children were living with them. Elizabeth (Lizzie) and Louisa were in their 30s and single. Burch was married to William Hulvershorn (incorrectly spelled by the census taker as Holosishorn) whose parents were German born. He was a 34 year old bookkeeper. He and Burch had been married for 12 years and had one child who died. A grandson, Clinton Ingels, was 16 years old. A 25 year old servant, Mollie Borger, completed the household. Her parents were born in Germany.

Daughter Mollie had married Charles Meininger 18 years prior and lived next door. They had no children. Hiram was living with his wife and three children on Laurel Street. George, Jr. was living with his wife of 21 years, Jennie M., and four of their five surviving children (out of a total of seven offspring), on Central Avenue. Jennie’s parents were German born. Clinton, the grandson living with George, Sr. and Mary, may have been the son of George, Jr. and Jennie.

George W. Ingels died on July 23, 1901 and was buried in the Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati. His wife followed him in death on May 24, 1907 and was buried beside him. All of their children remained in Cincinnati and were buried in the family lot at Spring Grove Cemetery.

George W. Ingels died on July 23, 1901 and was buried in the Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati. His wife followed him in death on May 24, 1907 and was buried beside him. All of their children remained in Cincinnati and were buried in the family lot at Spring Grove Cemetery.

Louisa Kleizer’s whereabouts between 1881 when she purchased an easement along an alley on one side of her property on Main Street in Paris, and when she died in Massachusetts is unknown but limited evidence suggests that she left Paris and moved to Springfield, Massachusetts where her daughter, Ellen Burch, was living with her husband, a white man named Charles Knight, and their children. Ellen, who went by the name Ella, also crossed the boundary between white and black. Her husband was a New Hampshire native who fought in Civil War with a New Hampshire company and was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for meritorious conduct at the Battle of the Crater. After the war, he worked as an armorer at the U.S. Armory until his death at age 65 on August 9, 1904. Charles and Ella had three daughters, Clara Louise born in February, 1879, Sarah Elizabeth born in July, 1880, and Laura Gertrude, born in July, 1883.

No record was found for Louisa Kleizer in the 1900 census in either Bourbon County or Massachusetts. Her death date was discovered in a deed that was filed when Ella Knight and her daughters sold Louisa’s property on Main Street in Paris in 1907. The deed stated that Louisa Knight had died intestate in Springfield, Massachusetts “about four years” earlier. The deed further confirmed that Ella Knight was her daughter. Ella Knight was the former Ellen Burch who lived with Louisa and Mary Kleizer in Paris and was listed as a mulatto female in the censuses of 1850, 1860 and 1870. The place of Louisa’s death was incorrect in the deed; she actually died in Northampton about 15 miles north of Springfield but was buried in the Oak Grove Cemetery in Springfield. Ella Knight made the same decision as her mother and aunt; she moved away from her Kentucky home and married a white man with whom she raised children who also identified as white.

Louisa and Mary Kleizer each made life-changing decisions that were heavily influenced by racial factors. Key to the decisions they made and actions they took was the fact that both of them were light-skinned. Had they had darker skin tones, there would have been no option for identifying as white for either of them.

The key dividing point in Mary Kleizer’s life seems to have been her relationship with George W. Ingels. George Ingels was from a very prominent, affluent Bourbon County family. His decision to become involved with a woman of color is unlikely to have been well received by his family. Sexual relationships between white men and women of color were, more often than not, coercive because most women of color were enslaved and avoiding predatory sexual behavior by white men was very difficult. But George and Mary’s relationship appears to have been, from the beginning, consensual and committed. Their relationship began after Mary and Louisa bought their property on Main Street in the same block where George was running a livery stable in 1850. Their first child was born in 1853 and five more children followed with the last child born in 1866. Census records indicate that all of the children were born in Kentucky. They could not have been legally married at this time since interracial marriage was prohibited in Kentucky and they may never have formally solemnized their relationship. While the children of white masters and enslaved women were often unacknowledged publicly (even though their paternal parentage was probably an open secret among the enslaved community), Mary’s children could not have gone unnoticed in Paris and their light skin color further marked them as racially mixed. It seems very likely that the association between George and Mary was no secret to many people.

George and Mary moved to Cincinnati with their six children sometime between December 1866 when their last child, Burch, was born and 1868 when George W. was first listed in a city directory. Mary and the children were categorized as mulatto in the 1870 census but by the 1880 census, only Mary was so classified while her children were all listed as white. Another notation in the family’s 1880 census record reveals that Mary reported her father’s birthplace as Germany and her mother’s as Virginia. Back in Paris, Louisa reported both her parents’ birthplace as Kentucky. However, if Mary was reporting truthfully, her father may have been Henry Kleizer, the man who directed that Mary’s mother be freed with her daughters after his death. In any event, the process to disassociate the Ingels children from their racial background seems to have been in play by 1880 although it seems inconsistent that the census taker would have acknowledged that Mary, a mulatto woman, was the mother and then classified her children as white. Normally, the racial definitions of the time dictated that any evidence of African heritage identified a person as Black or mulatto.

Between 1880 and 1900, Mollie, George W., Jr., Hiram and Burch all married white spouses that had German ethnic ties. The family’s affinity for privileging their German heritage seems significant and may have stemmed from Mary’s background. Ingels is generally considered to be of Anglo-Scandanavian origins but Kleizer is a common Jewish name and also occurs in Hungary. Germanic surnames among the spouses of the Ingels children include Meininger, Hulvershorn, Closs and Fehrman. Cincinnati’s population had a large Germanic component that would have provided many potential marriage partners. During this same time period, Mary Ingels seems to have been making a conscious choice to “pass for white” and she was so designated in the 1900 census. It seems likely that her husband, George, was complicit and encouraged the deception as well. Were her daughters- and sons-in-law aware of her racially mixed background? Even though Ohio was a northern state, repressive racial laws that barred black immigration into the state created a tense racial climate. Interracial marriage was not legalized in Ohio until 1887. No marriage record has been found for George and Mary Ingels although they clearly considered themselves married.

The decision to “pass for white” is not one that is made lightly. It often distances a person from his or her Black relatives and always carries the potential for exposure. Sociologist John H. Burma (1946:21, 22) makes the distinction that “passing is a matter of degree” and can be either permanent or “of a temporary and segmental nature.” People whose skin color allowed them to pass for white often did so without much censure from other African-Americans to “attain some temporary goal, such as a meal, concert, travel accommodations, or a service” at a time when public conveyances had segregated seating sections and some restaurants, stores and entertainment venues would not serve people of color. Permanent passing brought with it varied attitudes among the black community, ranging from complete condemnation to amusement in perpetrating a hoax against whites to acceptance on practical grounds. Mary’s motivation for permanently passing for white, if that is indeed what she did, may have been tied to her desire to enable her children to live as whites in a dominantly white society in addition to the benefits she derived for herself.

Louisa remained in the county of her birth for a much longer time than her sister and was racially identified as mulatto in every document that recorded her presence in Kentucky. However, when she relocated to Massachusetts, her transition from a woman of color to white seems to have taken place. Her daughter, Ella, was married to a white man who was a decorated Civil War veteran and had three daughters all of whom were classified as white in census and other records. Ella herself was identified as white in all records originating in Massachusetts. Her census record for 1900 indicates that she reported being married for 29 years. Although a formal marriage record has not been found, the census entry suggests that their relationship began around 1871. Their oldest child, Clara L., was born in Kentucky in 1879. Her birth may have taken place during a visit to Kentucky or the couple may have lived there for awhile. Their relocation to Massachusetts may have prompted Louisa to make the decision to leave Kentucky. While it is not clear exactly when Louisa left, it may have been between 1881 (the date of her purchase of an alley easement) and 1886 when her property on Main Street was occupied by two restaurants that may have been rented to their proprietors. In any event, Louisa retained ownership of her property in Paris and presumably supported herself with the rental income. Her omission in the 1900 census is puzzling but may simply be an oversight. Louisa died on December 17, 1902 in Northampton, Massachusetts of senility and pneumonia. Springfield was listed as her usual residence; Northampton is about 15 miles to the north. There was a sanatorium located in Northampton and since Louisa died of senility it is possible she was in the hospital there at the time of her death. She is buried in the Oak Grove Cemetery in Springfield where her daughter and family are also buried. Louisa’s death record confirms that her father was Henry Kleizer; her mother’s name is recorded as Julia rather than Judith with the surname Johnson. Oddly, Louisa’s record indicates that she was once married but the name of the husband is recorded as unknown.

Many questions go unanswered concerning the story of Mary Malvina and Louisa Warren Kleizer. What sort of relationship did their mother have with Henry Kleizer, the father of her children? How did George W. Ingels and Mary Kleizer negotiate the difficult racial climate in Kentucky after the Civil War as an interracial couple? What steps did Mary, Louisa and Ella take to make the transition from “colored” to white? Who was Louisa Kleizer’s husband? Who was the father of Louisa’s daughter, Ellen/Ella Burch? When did Louisa Kleizer leave Paris and why is her name missing from the 1900 census?

Sources:

- Ancestry.com website

- Bourbon County deed books, County Clerk’s office, Paris, Kentucky

- Samuel B. Kleizer to Henry Kleizer, July 20, 1833, Deed Book Z, p. 616

- William and Caroline P. Duke to Louisa and Mary Kleizer, May 29, 1850, Deed Book 44, p. 332

- George W. and Mary Ingels to Louisa Kleizer, October 27, 1880, Deed Book 65, p. 54

- Charles Henry and Louisa Singer to Louisa Kleizer, need date, Deed Book 65, p. 363

- Bourbon County manumission book, County Clerk’s office, Paris, Kentucky, deed of emancipation from John Kleizer to Jude and her daughters, Louisa Warren and Mary Malvina, July 4, 1836

- Burma, John H.

- 1946 The Measurement of Negro “Passing.” American Journal of Sociology 52 (1): 18-22.

- Historical Census Browser, 2004, Retrieved 13 November 2013, from the University of Virginia, Geospatial and Statistical Data Center: http://mapserver.lib.virginia.edu/collections/stats/histcensus/index.htm

- Inventory of Henry Kleizer, Bourbon County Will Book K, p. 204, June 14, 1836, County Clerk’s office, Paris, Kentucky

- Federal censuses, Bourbon County, Kentucky and Hamilton County, Ohio; various years

- Find-A-Grave website for George W. Ingels family

- Lucas, Marion B.

- 1992 A History of Blacks in Kentucky, Volume 1: From Slavery to Segregation, 1760-1891. Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, Kentucky

- Mapquest.com website

- Paris True Kentuckian, October 4, 1871 issue (Original at the Bourbon County Citizen/Citizen Adertiser office in Paris)

- Sanborn Insurance maps, Kentucky Digital Library website

- Toplin, Robert Brent

- 1979 Between Black and White: Attitudes Toward Southern Mulattoes, 1830-1861. The Journal of Southern History 45 (2):185-200

The Kleizer Main Street Property in Paris

Louisa and Mary Kleizer purchased part of In-lot 14 in Paris, Kentucky from William and Caroline P. Duke on May 29, 1850 for $800. Caroline Duke had received the property as an inheritance from the estate of John L. Hickman. In-lot 14 was located at the corner of Mulberry (now 5th) and Main Streets. The description of the property is misleading in that it suggests that their lot was at the corner when it actually was northeast of it. The description reads: “Begin at a point on Main Street in centre of division wall between house owned by William W. Hughes and that conveyed to Mary and Louisa Kleizer, 47 feet 9 inches from the corner of Main and Mulberry and running with Main to line of Peter Haley’s lot, then at right angles 107 feet 3 inches then to Mulberry Street.” The 1861 Hewitt map of Paris shows a long rectangular building at the corner of Mulberry and Main Streets and two much smaller buildings with square floor plans next to it on Main Street. The Kleizers’ building is either the second or third building from the corner.

Louisa and Mary Kleizer purchased part of In-lot 14 in Paris, Kentucky from William and Caroline P. Duke on May 29, 1850 for $800. Caroline Duke had received the property as an inheritance from the estate of John L. Hickman. In-lot 14 was located at the corner of Mulberry (now 5th) and Main Streets. The description of the property is misleading in that it suggests that their lot was at the corner when it actually was northeast of it. The description reads: “Begin at a point on Main Street in centre of division wall between house owned by William W. Hughes and that conveyed to Mary and Louisa Kleizer, 47 feet 9 inches from the corner of Main and Mulberry and running with Main to line of Peter Haley’s lot, then at right angles 107 feet 3 inches then to Mulberry Street.” The 1861 Hewitt map of Paris shows a long rectangular building at the corner of Mulberry and Main Streets and two much smaller buildings with square floor plans next to it on Main Street. The Kleizers’ building is either the second or third building from the corner.

The next map showing the property is the 1877 Beers Atlas. The second and third buildings from the corner have the street addresses of 37 and 36 Main Street and are much larger, both having a rectangular footprint. The fourth building from the corner at 35 Main Street may be flanked by a narrow alley on its northeast side. If this is the alley between In-lots 13 and 14 for which Louisa bought an easement in 1881, then her lot probably corresponds to 35 and 36 Main Street. Regardless, the difference in the building footprints between the 1861 and 1877 maps indicates that Louisa and Mary either replaced the original structure with another one or enlarged the house that was standing on the lot when they purchased it in 1850. The buildings probably provided both housing for the Kleizer household and a confectionery shop run by Mary and Louisa and later the fancy goods and notions shop run by Louisa.

from the corner have the street addresses of 37 and 36 Main Street and are much larger, both having a rectangular footprint. The fourth building from the corner at 35 Main Street may be flanked by a narrow alley on its northeast side. If this is the alley between In-lots 13 and 14 for which Louisa bought an easement in 1881, then her lot probably corresponds to 35 and 36 Main Street. Regardless, the difference in the building footprints between the 1861 and 1877 maps indicates that Louisa and Mary either replaced the original structure with another one or enlarged the house that was standing on the lot when they purchased it in 1850. The buildings probably provided both housing for the Kleizer household and a confectionery shop run by Mary and Louisa and later the fancy goods and notions shop run by Louisa.

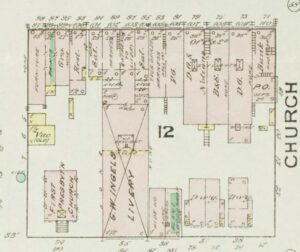

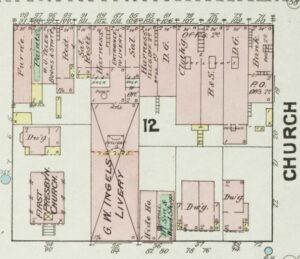

The Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of 1886 provides additional detail. Addresses had been renumbered along Main Street by 1886 and were undergoing another renumbering phase at the time the map was published. The brick building at the corner of Mulberry and Main Streets numbered 97/99 was a furniture store and shared a common wall with a paint store numbered 97/98. The next two buildings, numbered 95/99 and 93/100, were occupied by a grocery and a restaurant. An alley separated the restaurant from a saloon at 94/101 Main Street; this alley was the one for which Louisa purchased an easement in 1881. Although George W. Ingels had moved away from Paris in 1867, the livery stable next door to the Kleizers still bore his name in 1886. He may have rented it out to another proprietor.

The Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of 1886 provides additional detail. Addresses had been renumbered along Main Street by 1886 and were undergoing another renumbering phase at the time the map was published. The brick building at the corner of Mulberry and Main Streets numbered 97/99 was a furniture store and shared a common wall with a paint store numbered 97/98. The next two buildings, numbered 95/99 and 93/100, were occupied by a grocery and a restaurant. An alley separated the restaurant from a saloon at 94/101 Main Street; this alley was the one for which Louisa purchased an easement in 1881. Although George W. Ingels had moved away from Paris in 1867, the livery stable next door to the Kleizers still bore his name in 1886. He may have rented it out to another proprietor.

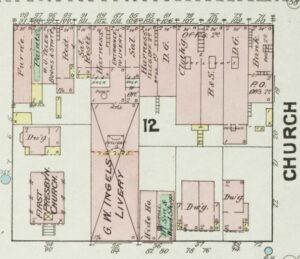

The 1890 Sanborn map shows few changes to the footprints of the buildings on the corner of Mulberry and Main but the grocery at 95/99 Main Street was replaced by a Western Union Telegraph office and books and stationery shop while adjoining building (93/100 Main) still held a restaurant. The changes in building function suggest that Louisa Kleizer may have been renting the buildings out and had already moved to Massachusetts by 1886. Alternatively, she may have been the proprietor of one of the businesses and rented the adjacent building out. The livery stable continued to operate under G.W. Ingels’ name in 1890.

Mulberry and Main but the grocery at 95/99 Main Street was replaced by a Western Union Telegraph office and books and stationery shop while adjoining building (93/100 Main) still held a restaurant. The changes in building function suggest that Louisa Kleizer may have been renting the buildings out and had already moved to Massachusetts by 1886. Alternatively, she may have been the proprietor of one of the businesses and rented the adjacent building out. The livery stable continued to operate under G.W. Ingels’ name in 1890.

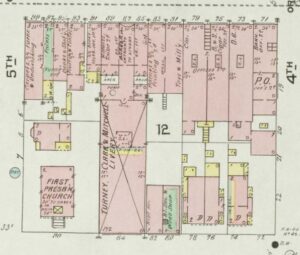

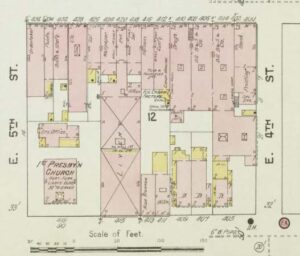

The 1896 Sanborn map shows the furniture and paint store on the corner at 99 and 97 Main Street. The furniture store description expanded to include carpets and undertaking. Books and stationery were still sold at 95 Main Street but the restaurant at 93 Main was replaced by a fruits and confections shop. Louisa had worked as a confectioner many years before and may have been running this shop but no corroborating evidence has been found to confirm this possibility. Louisa would have been 74 years old in 1896 and perhaps could have had sufficient rental income to live on but her exact whereabouts in the 1890s have not been determined. The livery stable had changed owners by 1896 and was operated by Turney, Clark and Mitchell. Mulberry Street was renamed 5th Street by 1896.

The 1896 Sanborn map shows the furniture and paint store on the corner at 99 and 97 Main Street. The furniture store description expanded to include carpets and undertaking. Books and stationery were still sold at 95 Main Street but the restaurant at 93 Main was replaced by a fruits and confections shop. Louisa had worked as a confectioner many years before and may have been running this shop but no corroborating evidence has been found to confirm this possibility. Louisa would have been 74 years old in 1896 and perhaps could have had sufficient rental income to live on but her exact whereabouts in the 1890s have not been determined. The livery stable had changed owners by 1896 and was operated by Turney, Clark and Mitchell. Mulberry Street was renamed 5th Street by 1896.

The 1901 Sanborn map shows no change in building function or footprint for the Main Street properties numbered 93, 95, 97 and 99 except that the fruits and confections shop is replaced by a plumber. The livery stable was operated by Walter Clark in 1901. It’s very probable that Louisa Kleizer was in Massachusetts by 1901. She may have made the move in 1900 which could account for her omission in the 1900 census.

properties numbered 93, 95, 97 and 99 except that the fruits and confections shop is replaced by a plumber. The livery stable was operated by Walter Clark in 1901. It’s very probable that Louisa Kleizer was in Massachusetts by 1901. She may have made the move in 1900 which could account for her omission in the 1900 census.

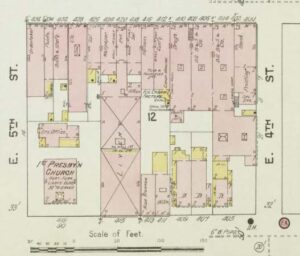

By 1907, Louisa Kleizer was deceased and the Main  Street property in Paris was owned by her daughter, Ella Knight, and her three daughters. Properties along Main Street had undergone another renumbering phase that applied current address numbers. The furniture store on the corner of E. Fifth and Main was now 436 Main and was occupied by an undertaker. The paint store at 434 Main was still in business as was the books and stationery shop on the Kleizer property at 432 Main. The plumber at 428 Main was replaced by a barber. The alley between In-lots 13 and 14 was still in place and the building footprints remained the same. W. M. Hinton, Jr. ran the livery stable next door.

Street property in Paris was owned by her daughter, Ella Knight, and her three daughters. Properties along Main Street had undergone another renumbering phase that applied current address numbers. The furniture store on the corner of E. Fifth and Main was now 436 Main and was occupied by an undertaker. The paint store at 434 Main was still in business as was the books and stationery shop on the Kleizer property at 432 Main. The plumber at 428 Main was replaced by a barber. The alley between In-lots 13 and 14 was still in place and the building footprints remained the same. W. M. Hinton, Jr. ran the livery stable next door.

The 1912 Sanborn map shows few changes in building functions for the Main Street properties or the livery stable but the building at 428 Main Street had either been replaced or significantly remodeled, eliminating the alley, extending the building length to about 100 feet and adding a skylight in the roof. Ella Knight and her daughters sold Louisa Kleizer’s property on February 19, 1910 to W. W. Mitchell and William Blakemore. The building was still operating as a barbershop run by Matt A. Cahal who lived upstairs with his family in 1910 but by 1912, a clothing store occupied the space.

barbershop run by Matt A. Cahal who lived upstairs with his family in 1910 but by 1912, a clothing store occupied the space.

W.W. Mitchell sold his interest in the property to H.O. James and W.R. Blakemore on March 8, 1928. It eventually was sold by H.O. James’ Heirs as part of his estate settlement in 1941 to Mamie S. and Carl O. Wilmoth and Minnie W. Goggin (widow). Carl Wilmoth was a real estate agent and Minnie Goggin was his sister. They probably bought the property as an investment. They conveyed it to John M. Stuart on March 1, 1944 who left it to the City Club of Paris in his will. The City Club currently occupies the building. The neighboring building has had many different functions during the 20th century. The two buildings on the corner were occupied by Daughterty’s Paint and Wallpaper Store under various proprietors for many years but the store closed with the death of the last owner, Dawes McCracken, and is now occupied by a dentist’s office.

Sources:

- Beers Atlas of Paris, Kentucky (1877)

- Bourbon County Deeds, Mamie S. and Carl O. Wilmoth and Minnie W. Goggin to John M. Stuart, Book 122, p. 630; Anna Boyd James & C.K. Thomas, Executor of H.O. James to Mamie S. Wilmoth and Minnie W. Goggin, Book 121, p. 358; W.W. Mitchell to H.O. James and W.R. Blakemore, Book 113, p. 447; Ella M. Knight, Clara Louise Knight, Sarah Elizabeth Knight and Laura Gertrude Knight to W. W. Mitchell and William Blakemore, Book 96, p 330; Ella M. Knight to Clara Louise Knight, Sarah Elizabeth Knight and Laura Gertrude Knight, Book 89, p. 495; George W. Ingels and Mary Kleizer Ingels to Louisa Kleizer, Book 65, p. 54; Charles Henry Singer and Louisa Singer to Louisa Kleizer, Book 65, p. 363; William and Caroline P. Duke to Louisa and Mary Kleizer, Book 44, p. 332.

- Bourbon County Will Book Y, p. 438, will of John M. Stuart.

- Hewitt topographical map of Paris, Kentucky (1861).

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps for Paris, Kentucky, 1886, 1890, 1896, 1901, 1907 and 1912.

Tracking Free Black Women in Bourbon County: the Intriguing Case of the Kleizer Women

By Nancy O’Malley, 2013

Free people of color in Bourbon County

Free people of color constituted a very small percentage of the African-American population in antebellum Kentucky. In Bourbon County where the African-American population was one of the highest in the state, women usually made up more than half of the free Black population in any given census year. However, free women of color never exceeded 3% of the total antebellum African-American population in Bourbon County. The minority status of free Blacks in Bourbon County placed them in a highly visible position since most people of color were enslaved and routinely identified by whites as the property of a particular slave owner. Free people of color, on the other hand, could not be so identified which placed them in a nebulous category—not enslaved but also not considered equal to whites.

Table 1. Census statistics for free people of color and the enslaved in Bourbon County, Kentucky

(2004) Historical Census Browser. Retrieved 13 November 2013, from the University of Virginia, Geospatial and Statistical Data Center: http://mapserver.lib.virginia.edu/collections/stats/histcensus/index.htm

When free Blacks appear in public records such as deeds, newspapers, probate documents and the like, their free status was invariably included by the use of terms such as “free colored” or “free man of color” or even, on occasion, attached to a name such as “free Betty.” Whites generally were suspicious of free people of color and harbored prejudicial attitudes that were no less and perhaps even more virulent than their attitudes about those enslaved (Lucas 1992:108). These attitudes hardened over time as slavery became increasingly equated with skin color and African ethnicity. Thus, free women and men of color had to negotiate a tenuous social ground. The situation was further complicated by the variation in skin color, ranging from very dark to very light complexions, that was present among enslaved and free people. These distinctions were expressed by terms such as black, mulatto, yellow, copper and very dark that were used as visual identity markers in runaway advertisements, manumission records or other documents along with descriptions of scars, facial shape or other observable bodily characteristics. Light-skinned people of color occupied an ambivalent racial position—neight white nor black enough to fit unambiguously in a clear-cut category. However, whites tended to view people with lighter skin color, free or slave, more favorably, considering them more capable of “refinement and advance…[and] more susceptible to improvement” (Toplin 1979:194).

The Kleizer Sisters

As part of a larger ongoing project to gather information about free people of color, particularly women, in Bourbon County, Kentucky, the existence of two sisters, Louisa Warren and Mary Malvina Kleizer, was uncovered. Their story is a particularly interesting one—partly because they owned property and were businesswomen in Paris and partly because both sisters eventually “passed for white”.

On June 14, 1836, an inventory was filed in the Bourbon County Court for blacksmith Henry Kleizer who had died intestate, probably on his farm of 147 acres on the Iron Works Road. The inventory included “1 Negro woman and 2 children” valued at $800. On July 4, 1836, Henry’s father, John Kleizer, acting on his son’s request, freed the woman, Jude, and her two daughters, Louisa Warren, and Mary Malvina in an order of manumission that was filed in the Bourbon County Clerk’s office. Jude was described as 42 years old, 5 ft ½ in in height, with a yellowish complexion, open countenance and “altogether rather good looking.” Louisa Warren was 14 years old, 4 ft 10 ½ in in height and Mary Malvina was 12 years old and 4 ft 7 in in height. Both were slender with “bright mulatto” complexions and “good countenances”. Their light skin color suggests that their ancestry included white relatives, most likely white fathers and one or more white grandparents.

Henry Kleizer also owned two enslaved boys, Washington and Silas, to whom he did not grant freedom. He had purchased the two boys, then 4 and 3 years old respectively, along with his farm of 147 acres from Samuel B. Kleizer in 1833. By 1840, Jude was using the surname of Kleizer and heading her own household with her two daughters. In 1840, Jude was one of 30 free women of color in Bourbon County between the ages of 36 and 54 years. Louisa and Mary were among 33 young free women of color between 10 and 23 years. There were only 160 free females in Bourbon County compared to 3144 enslaved females. Jude had to support herself and her daughters; her occupation is unknown but she probably held one of the limited occupations generally filled by women of color, such as cook, laundress, child care or perhaps agricultural labor. Sadly, Jude died of cholera in 1849, leaving her two daughters who by that time were in their 20s.

On May 29, 1850, Louisa and Mary Kleizer purchased a house and lot on Main Street in Paris for $800 from William and Catherine P. Duke. The lot was part of in-lot 14 near the corner of Main and Mulberry (now 5th) Streets. The property corresponds to 428 Main Street where the City Club is now located. The building was flanked by the property of William W. Hughes on the northeast side and Peter Haley on the southwest side. Louisa and Mary were occupying their newly purchased property when they were censused in 1850. Louisa was 24 years old and was not listed with an occupation nor could she read or write. Mary was 22 years old, also without an occupation, but was able to read and write. An 8 year old mulatto girl named Ellen Burch lived with the two sisters and had attended school during the year.

Living next door was Peter Haley, a 56 year old baker. Also living nearby was William Hughes, a 28 year old saddler. Listed with Hughes and his family was George W. Ingels, a 26 year old white stable keeper who owned real estate valued at $1300. His livery stable had an entrance on Main Street that led to the stable area in the rear of the lot which stretched to Pleasant Street. George W. Ingels was the son of Boone Ingels and Elizabeth Reid Ingels. Boone Ingels was born at Grant’s Station on Bryan Station Road near the Bourbon/Fayette County line to James Ingels, Jr. and Catherine Boone Dehart Ingels. George has a second listing under his mother’s household in the 1850 census. His father, Boone, died in 1837 and his mother never remarried. In 1850, she was listed in Paris with real estate valued at $7000. Her household included Edward, aged 28, who was a physician, George W., aged 26 who was not listed with an occupation but had real estate valued at $1300, Mary, aged 20, and Eliza Blandenberg, aged 23.

In 1867, Mary and George moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, leaving Louisa Kleizer and Ellen Burch in Paris. Williams’ 1868 Cincinnati Directory listed George W. Ingels as a partner in the firm Arnold, Bullock & Co. James L. Arnold, Thomas L. Arnold, W.K. Bullock and George W. Ingels were wholesale grocers, commission merchants and liquor dealers at 49 W. Front Street. In the 1869 directory, George was associated with J.L. Arnold in a coal dealership under the firm name of Arnold & Ingels.

George W. Ingels appears in the 1870 census for Cincinnati, Ohio, living with Mary who assumed his surname as did their children. Mary and her children are all identified as mulatto in this census. Two more children, Hiram, aged 8, and Birchie (a nickname for Burch), a daughter aged 5, had been born in Kentucky since the last census. Elizabeth and George had both attended school within the year, but Louisa was an invalid. George reported his occupation as a retired coal merchant worth $35,000 in real estate and $10,000 in personal estate at the relatively young age of 46.

assumed his surname as did their children. Mary and her children are all identified as mulatto in this census. Two more children, Hiram, aged 8, and Birchie (a nickname for Burch), a daughter aged 5, had been born in Kentucky since the last census. Elizabeth and George had both attended school within the year, but Louisa was an invalid. George reported his occupation as a retired coal merchant worth $35,000 in real estate and $10,000 in personal estate at the relatively young age of 46.

The 1870 census lists Louisa as a notions and fancy goods merchant, and Ellen Burch was working as her clerk. The shop was probably in the building Louisa owned on Main Street. Although the 1860 census indicated that Louisa had married within the year, no evidence was found to indicate that she had a husband and the census may have been in error. However, her husband may have been a slave who would not have been living with her. She is not listed with a husband in 1870; he might have died.

In October of 1880, George and Mary Ingels sold Mary’s half-interest in the Paris Main Street property to Louisa Kleizer for $900. Louisa was living by herself by this time and was listed as a widow without an occupation. No record of any marriage was found in the Bourbon County records for Louisa Kleizer.

The 1880 census record for the Ingels family chronicles a change in how the Ingels children were categorized. Although Mary is still listed as mulatto, all of her and George’s children are listed as white. The family was living on Hopkins Street at the time of the census and were still living there in 1890. All six of their children were living with their parents in 1880. The two oldest, Elizabeth, aged 22 and Louise, aged 18, helped their mother keep house. George at age 16 was a bill-clerk in a store. Hiram worked as an entry clerk. He was 17 years old but the census incorrectly lists his age as 22. Burch, aged 13, and Mollie, aged 9, both attended school. Burch was incorrectly identified as male. George, Sr. reported his occupation as a retired merchant.

Mary and George Ingels lived in Cincinnati for the rest of their lives. By 1900, they were living on Wesley Avenue just a few blocks from their former home on Hopkins Street. The census taker incorrectly spelled their name as Engalls. George reported that he was 76 years old, born in February of 1824 and married for 47 years. He was a landlord. His wife Mary was identified as white rather than mulatto. She was 75 years old, born in February of 1825. Oddly, the census taker listed Germany as the birthplace of both her parents. Other people in the household also had German born parents so this may have been a miscommunication with the census taker but given that Mary appears to be passing for white in this record, it may have been intentional. All of the family members in the household were listed as white. Three of George and Mary’s six children were living with them. Elizabeth (Lizzie) and Louisa were in their 30s and single. Burch was married to William Hulvershorn (incorrectly spelled by the census taker as Holosishorn) whose parents were German born. He was a 34 year old bookkeeper. He and Burch had been married for 12 years and had one child who died. A grandson, Clinton Ingels, was 16 years old. A 25 year old servant, Mollie Borger, completed the household. Her parents were born in Germany.

Daughter Mollie had married Charles Meininger 18 years prior and lived next door. They had no children. Hiram was living with his wife and three children on Laurel Street. George, Jr. was living with his wife of 21 years, Jennie M., and four of their five surviving children (out of a total of seven offspring), on Central Avenue. Jennie’s parents were German born. Clinton, the grandson living with George, Sr. and Mary, may have been the son of George, Jr. and Jennie.

Louisa Kleizer’s whereabouts between 1881 when she purchased an easement along an alley on one side of her property on Main Street in Paris, and when she died in Massachusetts is unknown but limited evidence suggests that she left Paris and moved to Springfield, Massachusetts where her daughter, Ellen Burch, was living with her husband, a white man named Charles Knight, and their children. Ellen, who went by the name Ella, also crossed the boundary between white and black. Her husband was a New Hampshire native who fought in Civil War with a New Hampshire company and was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for meritorious conduct at the Battle of the Crater. After the war, he worked as an armorer at the U.S. Armory until his death at age 65 on August 9, 1904. Charles and Ella had three daughters, Clara Louise born in February, 1879, Sarah Elizabeth born in July, 1880, and Laura Gertrude, born in July, 1883.

No record was found for Louisa Kleizer in the 1900 census in either Bourbon County or Massachusetts. Her death date was discovered in a deed that was filed when Ella Knight and her daughters sold Louisa’s property on Main Street in Paris in 1907. The deed stated that Louisa Knight had died intestate in Springfield, Massachusetts “about four years” earlier. The deed further confirmed that Ella Knight was her daughter. Ella Knight was the former Ellen Burch who lived with Louisa and Mary Kleizer in Paris and was listed as a mulatto female in the censuses of 1850, 1860 and 1870. The place of Louisa’s death was incorrect in the deed; she actually died in Northampton about 15 miles north of Springfield but was buried in the Oak Grove Cemetery in Springfield. Ella Knight made the same decision as her mother and aunt; she moved away from her Kentucky home and married a white man with whom she raised children who also identified as white.

Louisa and Mary Kleizer each made life-changing decisions that were heavily influenced by racial factors. Key to the decisions they made and actions they took was the fact that both of them were light-skinned. Had they had darker skin tones, there would have been no option for identifying as white for either of them.

The key dividing point in Mary Kleizer’s life seems to have been her relationship with George W. Ingels. George Ingels was from a very prominent, affluent Bourbon County family. His decision to become involved with a woman of color is unlikely to have been well received by his family. Sexual relationships between white men and women of color were, more often than not, coercive because most women of color were enslaved and avoiding predatory sexual behavior by white men was very difficult. But George and Mary’s relationship appears to have been, from the beginning, consensual and committed. Their relationship began after Mary and Louisa bought their property on Main Street in the same block where George was running a livery stable in 1850. Their first child was born in 1853 and five more children followed with the last child born in 1866. Census records indicate that all of the children were born in Kentucky. They could not have been legally married at this time since interracial marriage was prohibited in Kentucky and they may never have formally solemnized their relationship. While the children of white masters and enslaved women were often unacknowledged publicly (even though their paternal parentage was probably an open secret among the enslaved community), Mary’s children could not have gone unnoticed in Paris and their light skin color further marked them as racially mixed. It seems very likely that the association between George and Mary was no secret to many people.

George and Mary moved to Cincinnati with their six children sometime between December 1866 when their last child, Burch, was born and 1868 when George W. was first listed in a city directory. Mary and the children were categorized as mulatto in the 1870 census but by the 1880 census, only Mary was so classified while her children were all listed as white. Another notation in the family’s 1880 census record reveals that Mary reported her father’s birthplace as Germany and her mother’s as Virginia. Back in Paris, Louisa reported both her parents’ birthplace as Kentucky. However, if Mary was reporting truthfully, her father may have been Henry Kleizer, the man who directed that Mary’s mother be freed with her daughters after his death. In any event, the process to disassociate the Ingels children from their racial background seems to have been in play by 1880 although it seems inconsistent that the census taker would have acknowledged that Mary, a mulatto woman, was the mother and then classified her children as white. Normally, the racial definitions of the time dictated that any evidence of African heritage identified a person as Black or mulatto.

Between 1880 and 1900, Mollie, George W., Jr., Hiram and Burch all married white spouses that had German ethnic ties. The family’s affinity for privileging their German heritage seems significant and may have stemmed from Mary’s background. Ingels is generally considered to be of Anglo-Scandanavian origins but Kleizer is a common Jewish name and also occurs in Hungary. Germanic surnames among the spouses of the Ingels children include Meininger, Hulvershorn, Closs and Fehrman. Cincinnati’s population had a large Germanic component that would have provided many potential marriage partners. During this same time period, Mary Ingels seems to have been making a conscious choice to “pass for white” and she was so designated in the 1900 census. It seems likely that her husband, George, was complicit and encouraged the deception as well. Were her daughters- and sons-in-law aware of her racially mixed background? Even though Ohio was a northern state, repressive racial laws that barred black immigration into the state created a tense racial climate. Interracial marriage was not legalized in Ohio until 1887. No marriage record has been found for George and Mary Ingels although they clearly considered themselves married.

The decision to “pass for white” is not one that is made lightly. It often distances a person from his or her Black relatives and always carries the potential for exposure. Sociologist John H. Burma (1946:21, 22) makes the distinction that “passing is a matter of degree” and can be either permanent or “of a temporary and segmental nature.” People whose skin color allowed them to pass for white often did so without much censure from other African-Americans to “attain some temporary goal, such as a meal, concert, travel accommodations, or a service” at a time when public conveyances had segregated seating sections and some restaurants, stores and entertainment venues would not serve people of color. Permanent passing brought with it varied attitudes among the black community, ranging from complete condemnation to amusement in perpetrating a hoax against whites to acceptance on practical grounds. Mary’s motivation for permanently passing for white, if that is indeed what she did, may have been tied to her desire to enable her children to live as whites in a dominantly white society in addition to the benefits she derived for herself.

Louisa remained in the county of her birth for a much longer time than her sister and was racially identified as mulatto in every document that recorded her presence in Kentucky. However, when she relocated to Massachusetts, her transition from a woman of color to white seems to have taken place. Her daughter, Ella, was married to a white man who was a decorated Civil War veteran and had three daughters all of whom were classified as white in census and other records. Ella herself was identified as white in all records originating in Massachusetts. Her census record for 1900 indicates that she reported being married for 29 years. Although a formal marriage record has not been found, the census entry suggests that their relationship began around 1871. Their oldest child, Clara L., was born in Kentucky in 1879. Her birth may have taken place during a visit to Kentucky or the couple may have lived there for awhile. Their relocation to Massachusetts may have prompted Louisa to make the decision to leave Kentucky. While it is not clear exactly when Louisa left, it may have been between 1881 (the date of her purchase of an alley easement) and 1886 when her property on Main Street was occupied by two restaurants that may have been rented to their proprietors. In any event, Louisa retained ownership of her property in Paris and presumably supported herself with the rental income. Her omission in the 1900 census is puzzling but may simply be an oversight. Louisa died on December 17, 1902 in Northampton, Massachusetts of senility and pneumonia. Springfield was listed as her usual residence; Northampton is about 15 miles to the north. There was a sanatorium located in Northampton and since Louisa died of senility it is possible she was in the hospital there at the time of her death. She is buried in the Oak Grove Cemetery in Springfield where her daughter and family are also buried. Louisa’s death record confirms that her father was Henry Kleizer; her mother’s name is recorded as Julia rather than Judith with the surname Johnson. Oddly, Louisa’s record indicates that she was once married but the name of the husband is recorded as unknown.

Many questions go unanswered concerning the story of Mary Malvina and Louisa Warren Kleizer. What sort of relationship did their mother have with Henry Kleizer, the father of her children? How did George W. Ingels and Mary Kleizer negotiate the difficult racial climate in Kentucky after the Civil War as an interracial couple? What steps did Mary, Louisa and Ella take to make the transition from “colored” to white? Who was Louisa Kleizer’s husband? Who was the father of Louisa’s daughter, Ellen/Ella Burch? When did Louisa Kleizer leave Paris and why is her name missing from the 1900 census?

Sources:

The Kleizer Main Street Property in Paris

The next map showing the property is the 1877 Beers Atlas. The second and third buildings from the corner have the street addresses of 37 and 36 Main Street and are much larger, both having a rectangular footprint. The fourth building from the corner at 35 Main Street may be flanked by a narrow alley on its northeast side. If this is the alley between In-lots 13 and 14 for which Louisa bought an easement in 1881, then her lot probably corresponds to 35 and 36 Main Street. Regardless, the difference in the building footprints between the 1861 and 1877 maps indicates that Louisa and Mary either replaced the original structure with another one or enlarged the house that was standing on the lot when they purchased it in 1850. The buildings probably provided both housing for the Kleizer household and a confectionery shop run by Mary and Louisa and later the fancy goods and notions shop run by Louisa.

from the corner have the street addresses of 37 and 36 Main Street and are much larger, both having a rectangular footprint. The fourth building from the corner at 35 Main Street may be flanked by a narrow alley on its northeast side. If this is the alley between In-lots 13 and 14 for which Louisa bought an easement in 1881, then her lot probably corresponds to 35 and 36 Main Street. Regardless, the difference in the building footprints between the 1861 and 1877 maps indicates that Louisa and Mary either replaced the original structure with another one or enlarged the house that was standing on the lot when they purchased it in 1850. The buildings probably provided both housing for the Kleizer household and a confectionery shop run by Mary and Louisa and later the fancy goods and notions shop run by Louisa.

The 1890 Sanborn map shows few changes to the footprints of the buildings on the corner of Mulberry and Main but the grocery at 95/99 Main Street was replaced by a Western Union Telegraph office and books and stationery shop while adjoining building (93/100 Main) still held a restaurant. The changes in building function suggest that Louisa Kleizer may have been renting the buildings out and had already moved to Massachusetts by 1886. Alternatively, she may have been the proprietor of one of the businesses and rented the adjacent building out. The livery stable continued to operate under G.W. Ingels’ name in 1890.

Mulberry and Main but the grocery at 95/99 Main Street was replaced by a Western Union Telegraph office and books and stationery shop while adjoining building (93/100 Main) still held a restaurant. The changes in building function suggest that Louisa Kleizer may have been renting the buildings out and had already moved to Massachusetts by 1886. Alternatively, she may have been the proprietor of one of the businesses and rented the adjacent building out. The livery stable continued to operate under G.W. Ingels’ name in 1890.

The 1901 Sanborn map shows no change in building function or footprint for the Main Street properties numbered 93, 95, 97 and 99 except that the fruits and confections shop is replaced by a plumber. The livery stable was operated by Walter Clark in 1901. It’s very probable that Louisa Kleizer was in Massachusetts by 1901. She may have made the move in 1900 which could account for her omission in the 1900 census.

properties numbered 93, 95, 97 and 99 except that the fruits and confections shop is replaced by a plumber. The livery stable was operated by Walter Clark in 1901. It’s very probable that Louisa Kleizer was in Massachusetts by 1901. She may have made the move in 1900 which could account for her omission in the 1900 census.

By 1907, Louisa Kleizer was deceased and the Main Street property in Paris was owned by her daughter, Ella Knight, and her three daughters. Properties along Main Street had undergone another renumbering phase that applied current address numbers. The furniture store on the corner of E. Fifth and Main was now 436 Main and was occupied by an undertaker. The paint store at 434 Main was still in business as was the books and stationery shop on the Kleizer property at 432 Main. The plumber at 428 Main was replaced by a barber. The alley between In-lots 13 and 14 was still in place and the building footprints remained the same. W. M. Hinton, Jr. ran the livery stable next door.

Street property in Paris was owned by her daughter, Ella Knight, and her three daughters. Properties along Main Street had undergone another renumbering phase that applied current address numbers. The furniture store on the corner of E. Fifth and Main was now 436 Main and was occupied by an undertaker. The paint store at 434 Main was still in business as was the books and stationery shop on the Kleizer property at 432 Main. The plumber at 428 Main was replaced by a barber. The alley between In-lots 13 and 14 was still in place and the building footprints remained the same. W. M. Hinton, Jr. ran the livery stable next door.

The 1912 Sanborn map shows few changes in building functions for the Main Street properties or the livery stable but the building at 428 Main Street had either been replaced or significantly remodeled, eliminating the alley, extending the building length to about 100 feet and adding a skylight in the roof. Ella Knight and her daughters sold Louisa Kleizer’s property on February 19, 1910 to W. W. Mitchell and William Blakemore. The building was still operating as a barbershop run by Matt A. Cahal who lived upstairs with his family in 1910 but by 1912, a clothing store occupied the space.

barbershop run by Matt A. Cahal who lived upstairs with his family in 1910 but by 1912, a clothing store occupied the space.

W.W. Mitchell sold his interest in the property to H.O. James and W.R. Blakemore on March 8, 1928. It eventually was sold by H.O. James’ Heirs as part of his estate settlement in 1941 to Mamie S. and Carl O. Wilmoth and Minnie W. Goggin (widow). Carl Wilmoth was a real estate agent and Minnie Goggin was his sister. They probably bought the property as an investment. They conveyed it to John M. Stuart on March 1, 1944 who left it to the City Club of Paris in his will. The City Club currently occupies the building. The neighboring building has had many different functions during the 20th century. The two buildings on the corner were occupied by Daughterty’s Paint and Wallpaper Store under various proprietors for many years but the store closed with the death of the last owner, Dawes McCracken, and is now occupied by a dentist’s office.

Sources:

Category: Blog